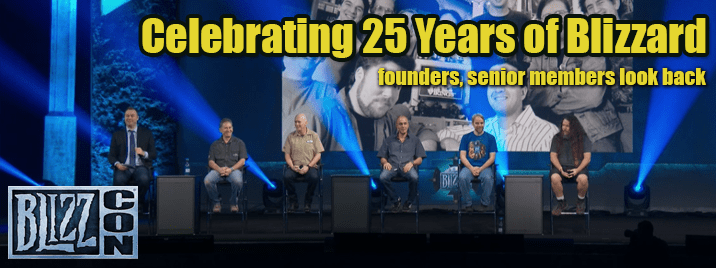

A Look Back at 25 Years of Blizzard

by Magistrate - 7 years ago show comments

As Blizzard looks back on its last 25 years as a company, several of its most senior members took the stage to share its history, and the many hats they’ve worn over the decades.

- Mike Morhaime, co-founder and current president, started with programming, purchasing, operations, and other responsibilities

- Frank Pearce, chief development officer, started with coding, occasionally working the reception desk in the old days, and now oversees current works in project

- Allen Adham, co-founder and senior vice president of new projects, first company president, and recently returned to company after 10 year “retirement;” before he left, he was lead developer on World of Warcraft

- Bob Fitch, engineering director, has done engineer work on almost every game (including Starcraft and Broodwar AI, early World of Warcraft balance, vanilla loot system, and combat system); most recently tech director of Hearthstone

- Samwise Didier, senior art director, has worked on almost every Blizzard title

Early Years

Blizzard wasn’t always a multi-franchise, multi-platform company employing hundreds. Adham is credited with first stepping up to found the company, alongside Morhaime, years ago. But a gaming company was a different thing in that confusing, weird time that was the early 90’s (and late 80’s). “A programmer could do all the art, sound effects, and publish by himself,” Adham recalled.

Adham started programming at 14, making his own games through high school and college. Shortly after graduation, he and Morhaime, as well as others, banded together in solidarity, with no business plan, to create a game company. Then, Blizzard make smaller games, and had to publish with outside publishers.

“In the first 3 years,” Adham said, “we were always only a week or so from bankruptcy.” Privately, he remembered thinking that there was only a fifty-fifty chance the company of (then) less than a dozen employees would survive its first year. However, the alternative was splitting the group up to work for companies like Microsoft, IBM, and others–not making games, presumably, or maybe just having a lot less fun.

“In the first 3 years,” Adham said, “we were always only a week or so from bankruptcy.” Privately, he remembered thinking that there was only a fifty-fifty chance the company of (then) less than a dozen employees would survive its first year. However, the alternative was splitting the group up to work for companies like Microsoft, IBM, and others–not making games, presumably, or maybe just having a lot less fun.

Morhaime recalled one of the most important lessons from the early days–distancing the team from their own work. “When you’re too close to your work,” he said, “you can’t see some problems,” such as with Lost Vikings. The small company created the game and shipped it off for publishing under Interplay.

Interplay’s president played it extensively, but returned with notes, feedback, and concerns about the art and difficulty of some levels. Allen had the team act on Interplay’s feedback, and the company has focused on responding to external criticism ever since, such as with open betas and testing on Private Test Realms (PTRs).

And getting into the company was a different process back then. Fitch recalled joining 10 months into the company’s founding–they needed a programmer for Rock ‘n’ Roll Racing. Through many levels of mutual connections, Fitch heard of the job, walking into a studio that was little more than an apartment. The tightly-knit community of ten welcomed Fitch’s less than professional attire and his zany attitude; Allen found him to be a perfect fit for the company’s culture.

Early Games

Many players think of the early Diablo or Warcraft titles when they think of Blizzard’s first games, but others, like Rock ‘n’ Roll Racing and Lost Vikings were some of their more exciting achievements before their franchises developed.

At the time, Blizzard, a newly formed, tiny company of less than a dozen members competed with big name companies like Sega, Konami, Capcom, and others. It would later arguably surpass them, but even back then they gave them a run for their money. Lost Vikings and Rock ‘n’ Roll Racing received puzzle game of the year and racing game of the year, respectively. In the same year.

Remember, this was before Blizzard was a publisher. Adham confided that to “justify” their roles as developers back then, they would often put obvious, weird stuff in their games when it came time for their publishers to review them. Wacky level backgrounds and quirks like random duck NPCs would distract the publishers from requiring other changes, and they would give the fledgling team an esteem boost, to boot.

Although these milestones were big for Blizzard back then, soon, everything would change.

Franchises Emerge

Over the years, Blizzard would come to be known for not one or two games, but entire franchises, including Diablo, Starcraft, Warcraft, and very recently, Overwatch. Extensions of these franchises would emerge much later, such as Heroes of the Storm and Hearthstone. Indeed, it became smart to see Blizzard not just as a single company, but separate, independently thinking and designing teams for each franchise, each one responsible for how best to design, implement, and maintain its franchise.

Soon, Chris Metzen came onto the scene, bringing to the table his world building concepts and a lot more. In 1994, Warcraft: Orcs and Humans released, a solid fantasy RTS on its own, and hype slowly grew. By the time Warcraft II released in December of 1991, the team started hosting midnight signing events at a local computer store.

Games back then were still hard copy releases (boxes and all), and still required an actual storefront. The early games featured things like notepads and drawing paper in the boxes–the last of which went out with Warcraft III, according to Didier.

Starcraft released in March of 1998. The team jokingly tossed around the idea of sending “dilithium crystals” (in reality, sand) with Starcraft‘s box, crystals to making additional pylons.

“People began watching the parking lot, seeing how many cars were left at night,” Morhaime recalled. The build-up to the release of Starcraft brought its own die-hard fans and what the old team referred to as “Operation CWAL”–that is, “Can’t Wait Any Longer.” Fans would come up with zany conspiracy theories about the state of the game, and strange fictional stories to rationalize the wait. Namely, that Adham and Morhaime had the finished copy of the game on a golden disc, but refused to let people play it due to “corporate reasons.”

“People began watching the parking lot, seeing how many cars were left at night,” Morhaime recalled. The build-up to the release of Starcraft brought its own die-hard fans and what the old team referred to as “Operation CWAL”–that is, “Can’t Wait Any Longer.” Fans would come up with zany conspiracy theories about the state of the game, and strange fictional stories to rationalize the wait. Namely, that Adham and Morhaime had the finished copy of the game on a golden disc, but refused to let people play it due to “corporate reasons.”

Conspiracies aside, Blizzard has always striven to be in touch with its committed fanbase. Then eSports happened.

Blizzard and Early eSports

Starcraft was a good game, but its largest audience wasn’t in the U.S.–it was in Korea. Morhaime and others arrived in Korea when the game hit the 2 million copy milestone for an event to commemorate the moment.

He arrived to an arena packed to the gills. From the edges of their seats, fans cheered and commented on every detail of Starcraft matches in the arena.

Warcraft began to develop its own eSports scene in China, but due to new laws forbidding video game footage to be shown on live TV, the country was “set back” a bit until the franchise–and the sport–further developed.

The Company Grows, World of Warcraft Arrives

Eventually, the team of less than a dozen creators, intent only on making great games and with little idea of what the future would hold, “exploded.”

It’s little secret that Blizzard gives out gifts to demarcate employees’ years of membership. Fitch once made it a necessity to personally know every member, but it eventually became unfeasible, and he develops the “sword rule;” that is, when an employee has been there for five years and earns their sword, he commits them to memory.

Warcraft as an RTS had three increasingly successful entries. The third (plus its expansion) were efforts to really flesh out the franchise for the shocker that would take the online gaming world by storm: World of Warcraft.

In late November of 2004, Morhaime and the others drove to the usual spot to sign midnight releases of the MMO, only to find the freeway choked and streets clogged. Perhaps thousands of fans arrived that night, making the developers find parking blocks away. Morhaime remembered wondering if another event was being held nearby.

The game would require the company’s complete focus for much of the decade, forestalling Diablo III and Starcraft II. In short, their business, and fanbase, were up for radical developments.

Morhaime recalled running out of boxed games numerous times. At one point, they had to redo their entire infrastructure to accommodate copies flying off the shelves. Their servers weren’t intended for the popularity World of Warcraft found.

(Ironically, Electronic Arts laughed the team out of the office when they tried to estimate launch users. They guessed a million, with no real research or backup. I guess we see who had the last laugh there.)

The Future

Years later, titular entries of their other franchises would finally get some light. Developments in technology, a growing employee base, radical fans, and many “miracles” combined to a lot of pay off for risky creative efforts.

Overwatch in particular was big for Blizzard. The team working on it had just come off the heels of a big defeat: project Titan had amounted to a game that was just, well, not fun, and it was scrapped. The team was so excited for the new ideas Overwatch presented–both stylistically and as a new genre for the company–that they brought it to life with vigor.

“One of my top favorite moments was the announcement of Overwatch,” Morhaime recalled. There’s always the all-to-common problem of leaks and spot-on speculation before a major game development is announced, and Overwatch was a tightly kept secret. When the cinematic went live at BlizzCon 2015, a story of triumph after years of trying to get Titan to work.

The fan community continues to be as vibrant as ever, and their art, content, and other creations have been leverage for employment over the years.

“There’s a ton of art globally, a lot of it better than what we can produce,” Didier recalled. In one instance, they hired an artist out of Australia, now working on units in Heroes of the Storm, who had outdone concept art reveals for all of the Starcraft units before he was hired.”Create it, and we’ll see it,” he continued. “Put it on all the social media sites.”

“There’s a ton of art globally, a lot of it better than what we can produce,” Didier recalled. In one instance, they hired an artist out of Australia, now working on units in Heroes of the Storm, who had outdone concept art reveals for all of the Starcraft units before he was hired.”Create it, and we’ll see it,” he continued. “Put it on all the social media sites.”

In another case, Morhaime had arrived to a show in China when Wei Wang, now an artist for many major projects including Warlords of Draenor and Legion, approached him. He presented his portfolio, containing amazing works of art, stating that he would love to work for Blizzard. To date, he’s also worked on art for the official movie, as well as other games.

Engineers and designers were hired based on maps they designed. Jeff Kaplan, vice president and game director of Overwatch, was one the guild master of Legacy of Steel, where many Blizzard employees put their World of Warcraft characters. Alex Afrasiabi, creative director for World of Warcraft, was once the guild master of Fires of Heaven.

Blizzard’s games continue to inspire and bring players together, and sometimes, that brings them to Blizzard. Here’s to 25 more years!